Editor’s Note: We’ve removed our paywall from this article so you can access vital coronavirus content. Find all our coverage here. To support our science journalism, become a subscriber.

COVID-19 will probably be a part of our lives for the foreseeable future. A vaccine has yet to materialize. As the pandemic continues to take a crushing toll, doctors are resorting to a century-old treatment that has been helpful in managing previous pandemics: taking antibodies from those who have recovered and giving it to the sick. It’s known as convalescent plasma therapy, or “survivors’ blood.”

Plasma — the liquid component of blood — contains antibodies. Extracting plasma from someone that has “convalesced,” or recovered, from an illness might provide a much-needed boost to the immune system of someone grappling with coronavirus.

In the past, plasma therapy has been a weapon against the 1918 flu, polio, measles, rabies, hepatitis B and Ebola — with varying levels of success. More recently, it showed some promise in treating other coronaviruses like SARS and MERS, particularly when given to a patient early in their illness.

There’s reason to be hopeful that plasma therapy can also help battle SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Preliminary studies have found that many patients who received plasma therapy improved. For instance, a trial of 31 severely ill patients from the University of Wisconsin-Madison improved enough to avoid the ICU or a ventilator after receiving plasma. Four patients still died, however.

As scientists and doctors continue to learn about plasma therapy, so will the public. A number of clinical trials are underway and can be viewed on clinicaltrials.gov.

In the meantime, the FDA has green-lighted plasma as an “emergency investigational new drug.” Soon, the agency may authorize it for wider use.

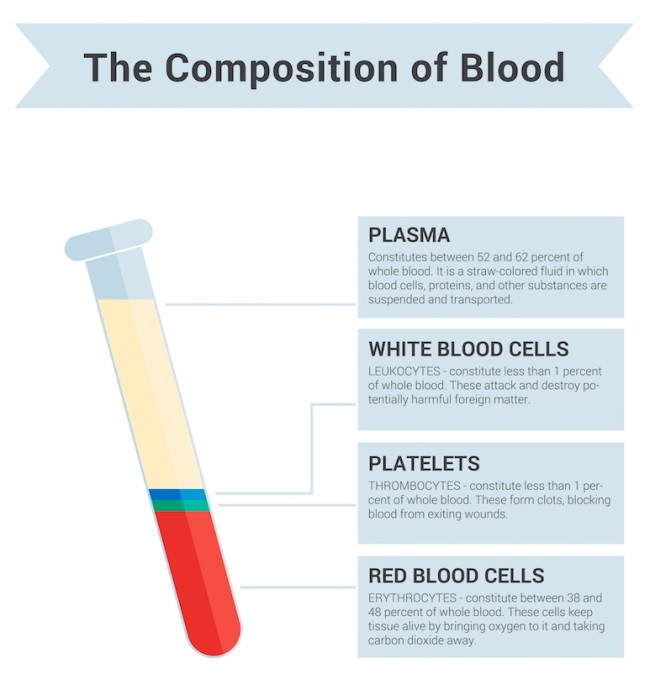

Blood is made of four main components. Red blood cells carry oxygen around the body, white blood cells support immune function, and cell fragments called platelets form clots to stop bleeding. The liquid portion is plasma and comprises a little more than 50 percent of blood volume.

(Credit: VasutinSergey/Shutterstock)

Plasma helps circulate proteins, nutrients and hormones throughout the body. But scientists are interested in plasma as a COVID-19 treatment because the substance contains antibodies after an infection. These protective proteins can bind to the surface of an antigen, or a foreign invader, and help the immune system dismantle it.

A plasma transfusion involves removing some antibodies from one person and infusing them into someone who is sick, providing an immediate jolt to their immune system. A dose of antibodies doesn’t directly stimulate a person’s immune system to start creating their own antibodies, but it does offer some protection until their own immune system ramps up.

Mounting an antibody response isn’t exactly a speedy process. It generally takes one to three weeks for the immune system to produce antibodies against COVID-19.

Ultimately, plasma therapy might shorten the length of illness and reduce the severity of the disease. Taken together, it may prevent some of the organ damage and acute respiratory distress complications that develop in a small number of patients.

Other scientists have proposed using survivors’ blood as a way to prevent coronavirus infection in the first place, but much more research is needed into how this might work.

It’s also important to keep in mind that plasma therapy is not a vaccine. Vaccines use the immune system’s memory response to train it to detect and respond to specific pathogens.

Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins produced by B-cells of the immune system to help fight bacteria and viruses. A diverse troupe of 10 million B-cells circulates in our bodies. Each type carries receptors for specific threats and secretes antibodies that can bind to antigens, found on the surface of pathogens. When a B-cell encounters its matching antigen, it pumps out distinct antibodies that can neutralize harmful invaders, or mark them for destruction by other immune system cells — namely T-cells.

Some B-cells transform into memory B-cells that remain on the lookout for the pathogen, ready to pump out antibodies again. Much less is known about the role of T-cells in lasting immunity. But scientists have a hunch that memory T-cells — which can remember past infection agents and kill them if they reappear — also provide protection against COVID-19.

Since the coronavirus is new, most uninfected people probably don’t have strong immune defenses built up already. But a recent study showed that some people who haven’t been exposed to the new coronavirus already had T-cells against the virus in their system. This suggests exposure to some other coronaviruses out there (like the common cold) may provide some people’s immune systems with a head start on fighting the new virus.

So, even though coronavirus antibodies might begin to fade within two to three months, it might not matter much in terms of long-term immunity.

Right now, there simply isn’t enough convalescent plasma to go around. An uptick in cases in many parts of the United States this summer has caused an emergency shortage of convalescent plasma. The American Red Cross is urging people who recovered from COVID-19 to donate their plasma to help treat the sick.

(Credit: Anna Fedorova_it/Shutterstock)

While many patients receiving plasma do seem to improve, it’s not always clear why. Over the course of their illness, patients might have received other therapies, like the antiviral Remdesivir or the steroid Dexamethasone. That makes it difficult to definitively say which treatments, or which combinations, deserve the kudos. Additionally, given the circumstances of the pandemic, many studies aren’t following gold-standard research protocols. A lot of what is known about plasma and COVID-19 has come from small studies that are not randomized, don’t include control groups as comparisons, and might not incorporate measures to account for things like the placebo effect.

At the same time, scientists are looking for ways to harness immune system cells to produce better plasma therapies. Not all antibodies have equal virus-fighting power. Neutralizing antibodies, which can directly dismantle a pathogen, are the most beneficial, yet hard to come by. A recent study of 150 people found that 1 percent of coronavirus survivors had high levels of neutralizing antibodies in their plasma, which was collected an average of 39 days after the onset of symptoms. Scientists think they might be able to capture and clone the elite B-cells that produce these antibodies and use them as the basis for more effective treatments.

A business can develop in many ways. One of the best ways to grow your…

American families are once again juggling the seasonal custom—and financial burden—of back-to-school shopping as the…

Want to bond over unexpected activities? Look at these unconventional ways to connect with your…

Burnout isn’t just something that happens to CEOs. For moms homeschooling littles, it’s a very…

When it comes to long-distance motorcycling, comfort, reliability, and smart engineering can make or break…

Flowers have seen significant transformation over time; online flower shopping is increasingly common now for…