To most Westerners, the Silk Road conjures images of exoticism: caravans of spices and silks, open-air markets filled with brightly-clothed hawkers and merchants, rolled carpets stacked high, turbaned travelers and monks from mountain monasteries.

To someone from the historical East, encompassing central, south and south-east Asia, the legendary trade route that linked the two civilizations would have done the same, if in reverse. Knights and Roman legionnaires, castles and Christianity — foreign concepts carried by traders and missionaries from the mysterious lands past the Eurasian Steppes.

Today, the legacy of the Silk Road is not the goods it carried but the philosophies and technologies that came with them. For the first time, the inhabitants of two very different worlds mingled and exchanged ideas, languages and artistry. Christianity flowed eastward, while Buddhism diffused out of India. Gunpowder and paper were introduced to Europe,

and Roman glass travelled eastward. In the middle, people and philosophies mixed, leading to the development of new cultures and ways of life fed by the influence of both the Western and Eastern worlds.

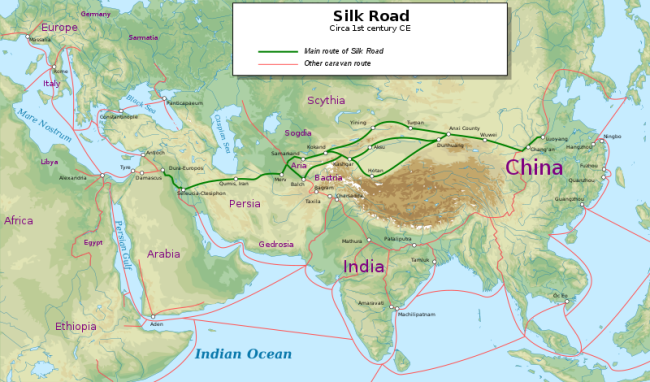

The Silk Road as a concept dates back only to the 19th century, when the term was popularized by a German explorer, Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen. Prior to that, there was no singular term for the trade routes that spanned Europe and Asia. The Silk Road itself was actually a number of different trade routes that, combined, serve to move goods from China to the Arabian Peninsula and farther west. Few merchants actually travelled the entire 4,000-mile-long route — goods were instead passed between intermediaries. Several travelers, such as Venetian explorer Marco Polo and Mongol diplomat Rabban Bar Sauma, did actually traverse much of the Silk Road’s breadth, returning valuable information about the civilizations on the other end, but they were the exception.

Credit: User:Kaidor/Wikimedia Commons

What we call the Silk Road today began to take shape during the Chinese Han dynasty, around the 2nd century B.C. After subduing the nomadic Xiongnu tribes to the north and west, the Han began colonizing new territory and expanding their relationships with outside

peoples. This involved sending envoys, like the Han ambassador Zhang Qian, expand diplomatic relationships and gather information on new lands. Qian’s travels laid the groundwork for subsequent expansions westward and new and valuable trade networks. The Han expanded the Great Wall of China, in part to protect caravans from bandits, and began promoting the flow of goods into and out of China. In particular, the Han were looking for strong horses to supply their military with, bartering with silk and other specialties.

Ferried by traders around forbidding deserts, mountain ranges and vast steppes, goods like silk, jade, spices, gems and, oddly enough, rhubarb (it was prized for its medicinal properties), began moving westward. Long caravans of camels, each carrying as much as 300 pounds, travelled between waystations in oasis cities like Balkh, Samarkand, Turfan and Kucha, hoping to avoid predation by bandits and punishing sandstorms.

Eventually, the goods would make their way into the growing Roman empire, whose wealthy citizens began developing a taste for exotic fineries, silk in particular. Roman products traveled far and wide as well. Roman glassware has turned up in a Japanese tomb, and glass beads from Rome have also been found in China.

A bronze rhinoceros with gold and silver inlays from the Han Dynasty, on display in the Beijing National Museum in 2008. (Credit: Gary Lee Todd/Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to the overland Silk Road trade route, there was also a burgeoning maritime route that linked East and West, beginning in Chinese ports, stopping off in Sri Lanka and India and and moving up the Red Sea to Egypt, and responsible for much of the spice trade. The overland route began in the city of Xi’an, moved west to parallel the Great Wall, skirted the harsh Taklamakan desert by both northern and southern routes and continued west through Samarkand, into modern-day Turkey and the Levant. Spurs split off into India, where many Chinese Buddhists travelled to access ancient texts, into northern Africa and to Constantinople and then Greece.

Trade along the Silk Road continued for roughly two thousand years, waxing and waning at times as the territories it traveled through shifted hands. Trade was particularly robust during the Tang dynasty, as well as the later Mongol empire, when Genghis Khan and his

successors unified most of Asia under one rule. Only with the dissolution of the Mongol empire did the Silk Road begin to fall apart, though trade between East and West continued for centuries.

Though the Silk Road’s wares originated on either end of its length, much of the actual trading was done by the people who lived in the middle. Most notable among these are the Sogdians, a central Asian civilization with the good fortune to sit in the midst of the vibrant trade route. Sogdian caravan merchants traveled far and wide along the Silk Road, and the Sogdian language appears to have been used as a common tongue along the route. Along

with their wares, the Sogdians likely helped spread different religions as they went, introducing Buddhism and a form of Christianity to China, and Islam to the Turks.

Today, the Silk Road is most notable for intermingling ideas and philosophies from different places. This led to new variations on religions, such as Nestorian Christianity, as well as to fundamental changes in culture, like when Buddhism was introduced to China.

A statue of a Sogdian traveler on a camel from the Tang Dynasty era, on display at the Shanghai Museum in 2005. (Credit: Airunp/Wikimedia Commons)

The Silk Road was also responsible for broadening cultural horizons wherever it went. Accounts such as The Travels of Marco Polo introduced European audiences to the wonders of China (though not always truthfully), and Rabban Bar Sauma’s writings offer a thoroughly-documented account of medieval Europe through the eyes of an outsider.

We can find the legacy of the Silk Road in human DNA today, as well. Studies of modern-day humans find evidence of genetic intermingling between Europeans and Asians in central Asia, which formed roughly the middle of the Silk Road. In addition to physical goods, it’s clear that the trade route also brought people far from their homes to settle in foreign locations, bringing their culture with them. From that melting pot, new traditions and peoples emerged, formed at the confluence of powerful civilizations.

Roofing is a crucial aspect of a building's structure as it protects the interior from…

When it comes to maintaining a home, one of the most important aspects to consider…

Galveston, Texas, is quickly emerging as a premier destination for deep-sea fishing enthusiasts in search…

In the ever-evolving landscape of construction and building maintenance, sustainability has emerged as a crucial…

Minnesota, celebrated for its picturesque rural landscapes and vibrant urban centers such as St. Paul…

In the realm of kitchen renovations, cabinetry plays a pivotal role in shaping both the…