“Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) is less read than his famous Walden, but easily as good. Nothing much happens there: Thoreau and his brother take a boat and sail up and down the two rivers. But what they see as they glide by (old cemeteries, churches, animals, plants, rocks) triggers a series of meditations about various things: history, religion, time (geological and historical), mourning, the dead, renewal of life (spiritual and biological), friendship, and other ways of being with others. It seems to me particularly relevant for our current moment of life in isolation: for the book is above all about taking leave of society at large to live in the company of two, but only in order to find a way back to living among others in a truly meaningful and responsible way.”

Her second choice is a meditation on mortality. “Whitman’s Specimen Days (1882), is a series of vignettes he wrote (mostly) about the Civil War wounded and dying in the hospitals in and around Washington, DC. He calls them ‘unnamed, unknown’, ‘Bravest Soldiers’ and narrates their ‘first-class desperations’, and ‘the sudden partial panic of the afternoon, at dusk’ before death, as additional acts of their extraordinary courage. It is also an important book for this moment, when we have lost so many to a global pandemic, and although we encounter those lost mostly as a number, we can perhaps begin to understand the pain via Whitman.”

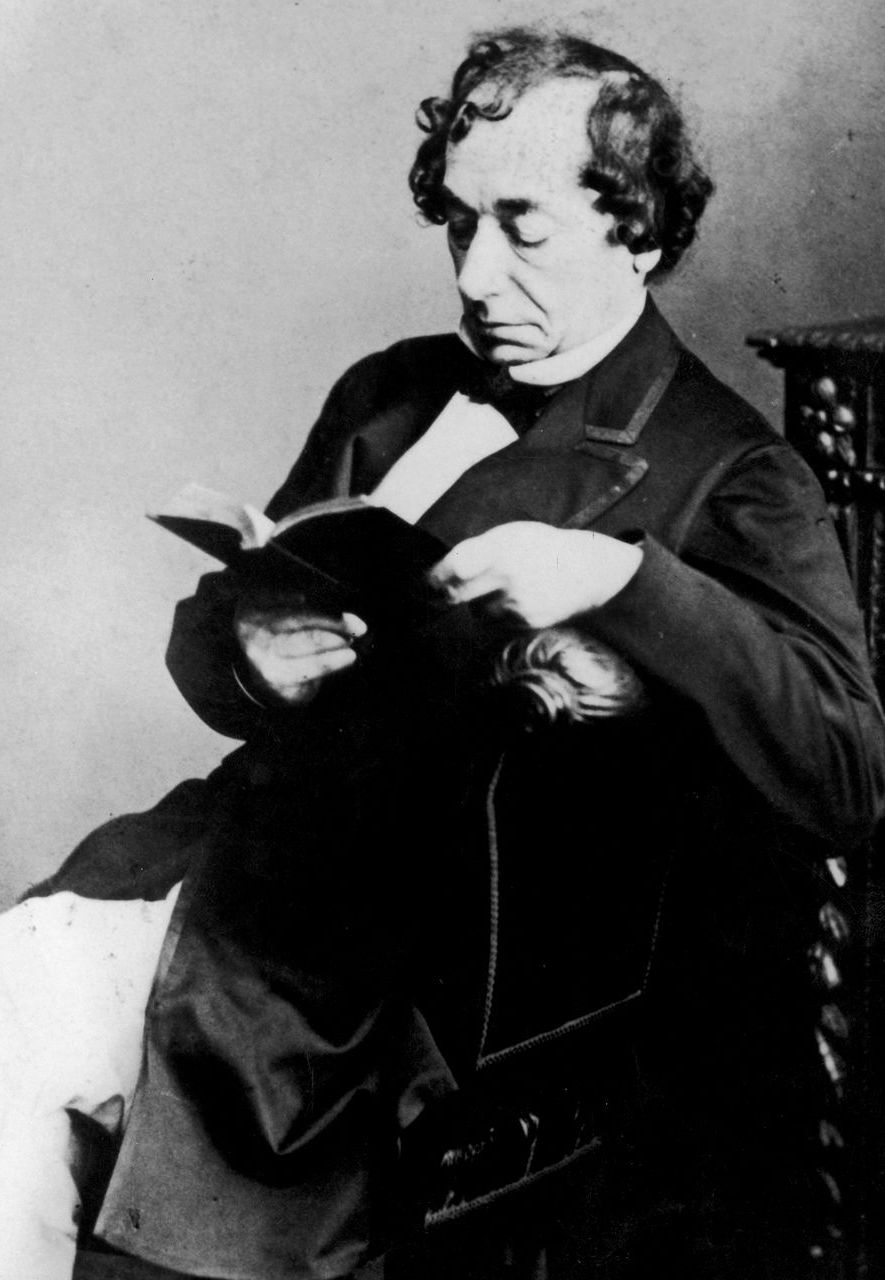

“Melville’s Confidence Man (1857) was called ‘crazy’ by some reviewers when it was published. It isn’t an easy read, but it is a revealing and disconcerting look at questions of trust, credibility, philanthropy, religious belief, exploitation, racism, and, more generally, the value of human life that is prophesied by all, but, at least on this novel’s account, rarely acted upon.”

Japan

Stephen Dodd is a professor of Japanese literature at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. He said: “In fact it is only in the mid-1880s that the idea of a long novel began to be explored in Japan and, I would say, it is only in the early 20th Century that the novel really begins to develop (as for instance with Natsume Soseki’s novel Kokoro). In the 19th Century there were certainly some interesting writers, but they tended to write short stories. The Japanese word for novel is ‘shosetsu‘, but this term covers anything from a few pages to hundreds of pages. Actually, the Japanese are particularly good at short stories.”

Accordingly, Professor Dodd recommends Higuchi Ichiyo, a woman short-story writer, born 1872, who is very famous in Japan, a good edition of whose work is In the Shade of Spring Leaves. An interesting male writer working in the same period is Kunikida Doppo; try River Mist and Other Stories. He adds: “To my mind, much more interesting are slightly later short stories by writers such as Izumi Kyoka” (for example, Japanese Gothic Tales). “A really entertaining story written before westernisation really took a grip was Shank’s Mare by Ikku Jippensha”, a picaresque tale issued serially in the early part of the 19th Century, and which concerns a journey along the highway between Tokyo and Kyoto.