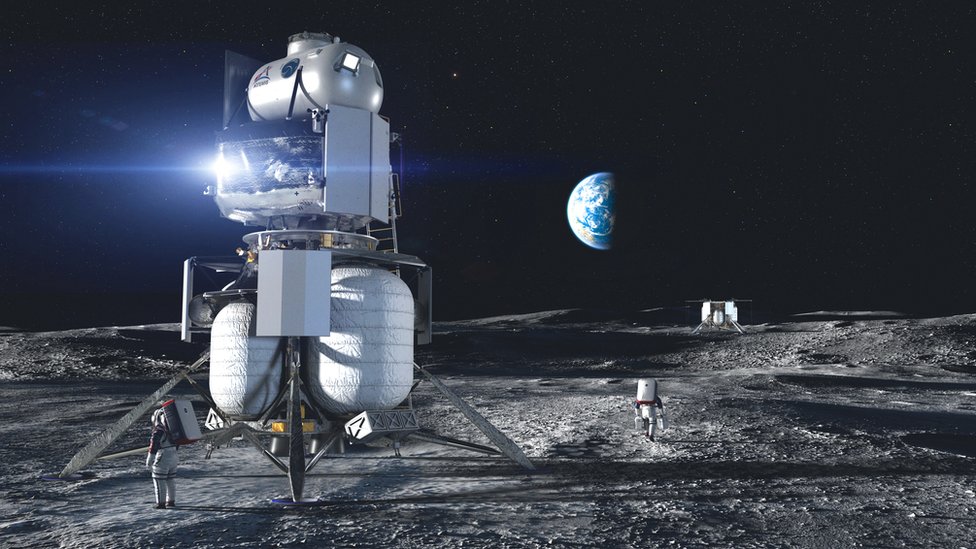

image copyrightBlue Origin

The UK has signed up to the principles that will guide the American-led return to the Moon this decade.

The US plans to put the first woman and the next man on the lunar surface in 2024, in a project called Artemis.

This would mirror the Apollo missions of the 1960s/70s but with the difference this time that astronauts would set up a permanent presence.

The so-called Artemis Accords are intended as a framework for best practice in space and on the Moon.

They cover areas such as the utilisation of resources, mining water-ice for drinking water and to make rocket fuel; common standards, open data, safe operations, and providing emergency assistance.

image copyrightNASA

The US space agency (Nasa) and the European Space Agency (Esa) are preparing a Memorandum of Understanding on their partnership activities at the Moon.

“It is very important that we have standards that we all adhere to when we explore space together,” Nasa administrator Jim Bridenstine told BBC News.

“And that’s not just in space in general, but also on other celestial bodies like the Moon and eventually Mars. The Artemis Accords are about those foundational principles that we all agree on, so that when we go explore these worlds together, there’s a commonality of purpose.”

The accords, said Mr Bridenstine, were grounded in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which committed nations not to put weapons in space and to forego claims of ownership.

Britain was a key mover behind that landmark resolution – just as it was three decades later when it became an original signatory to the cooperation principles on the International Space Station.

image copyrightESA

Britain is now seeking a number of roles in Artemis for its scientists and industrial sector. These include contracts to help build a lunar space station to be known as the Gateway.

This will be the jumping off point for astronauts as they shuttle back and forth to the Moon’s surface.

The British firm Surrey Satellite Technology Limited is also developing a communications relay satellite at the Moon called Lunar Pathfinder.

Not all spacefaring nations will sign the Accords. China very much does its own thing in space; and Russia too has indicated that Artemis, for the moment at least, is not part of its planning. This despite being a key partner to the US on the ISS.

“Our American partners are actively promoting [Artemis]. In our view Lunar Gateway in its current form is too US-centric. Russia is likely to refrain from participating in it on a large scale,” said Dmitry Rogozin, the head of the Russian space agency Roscosmos.

“This being said, we are interested in making sure that the design of the docking module will enable [Russia’s future Orel crew] spacecraft to dock to the Lunar Gateway.”

Some experts working in the area of international relations and space law have also questioned whether the accords are too focused on US interests, in a way that could lead to disagreements in the far future, especially if, or when, commercial interests overtake today’s scientific exploration.

Dr Alice Bunn is international director of the UK Space Agency. She said legal advice had been sought – along with clarifications from the Americans – before Britain signed the accords.

She cited as an example the idea that operators on the Moon could establish “safety zones” around their activities.

“We agreed with the principle but didn’t like the fact that this could be something that might be enduring in nature, and that could somehow be seen to be an appropriation of the Moon’s surface,” she told BBC News.

“The compromise we’ve arrived at is to make sure that these are temporary measures. So, they’re necessary, because we want to make sure that we’re not disrupting each other’s experiments, but they are temporary in nature and not enduring.”