S

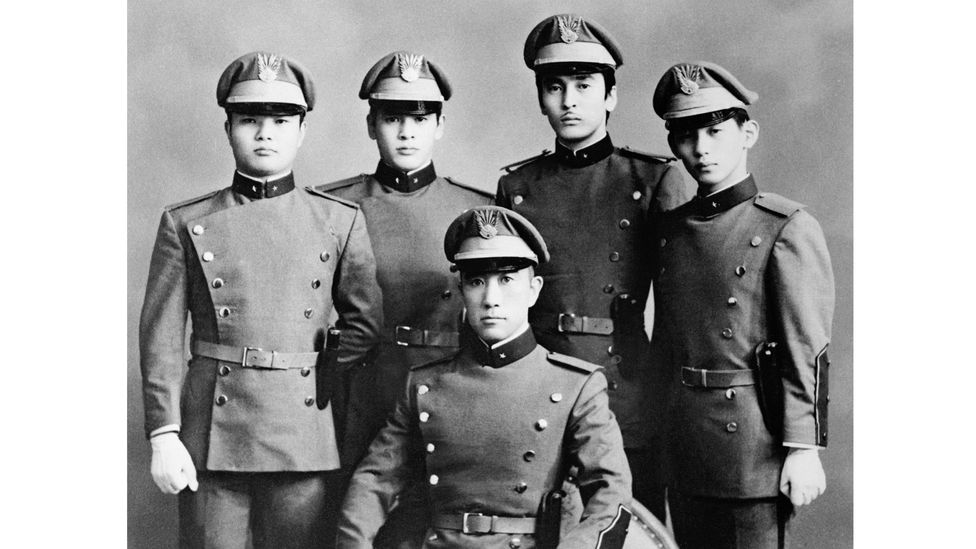

Standing on a balcony, as if on stage, the small, immaculate figure appeals to the army assembled below. The figure is Yukio Mishima, real name Kimitake Hiraoka. He was Japan’s most famous living novelist when, on 25 November 1970, he went to an army base in Tokyo, kidnapped the commander, had him assemble the garrison, then tried to start a coup. He railed against the US-backed state and constitution, berated the soldiers for their submissiveness and challenged them to return the Emperor to his pre-war position as living god and national leader. The audience, at first politely quiet, or just stunned into silence, soon drowned him out with jeers. Mishima stepped back inside and said: “I don’t think they heard me.” Then he knelt down and killed himself by seppuku, the Samurai’s ritual suicide.

More like this:

– The mysterious appeal of the labyrinth

– Why don’t we appreciate funny writing?

Mishima’s death shocked the Japanese public. He was a literary celebrity, a macho and provocative but also rather ridiculous character, perhaps akin to Norman Mailer in the US, or Michel Houellebecq in today’s France. But what had seemed to be posturing had suddenly become very real. It was the morning of the opening of the 64th session of the Diet, Japan’s parliament, and the Emperor himself was present. The prime minister’s speech on the government agenda for the coming year was somewhat overshadowed. No one had died by seppuku since the last days of World War Two.