Around 10 p.m. last Thursday, I received a call from a friend. The two of us primarily text, so a call was out of the ordinary. I picked up immediately, assuming it was an emergency.

She told me that a friend of a friend —a health-care worker who was distributing covid-19 vaccines that evening— was looking for people who wanted one. A freezer containing 1,600 doses of the Moderna vaccine had just gone down. The Moderna vaccine is based on new mRNA vaccine technology, which has unique refrigeration requirements: it must be stored at between -25°C and -15°C (-13°F and 5°F). Once it starts thawing, it has to get into people’s arms within a matter of hours. Once its short shelf life of 12 hours is over, it has to be tossed.

I live in Seattle where the vaccine rollout, like in the rest of the US, has been chaotic. Health-care workers have had to contend with ever-changing guidelines on whom to vaccinate and the availability of doses.

As of last week, the state was in the midst of vaccinating high-risk healthcare workers, first responders, and residents and staff of community-based, communal living settings, and had recently expanded to vaccinating everyone age 65 and older, or those over 50 living in multigenerational households.

Although the hospital staff was trying to call those who had priority, most of them were elderly would probably be asleep by then, so they were also creating a backup list. She asked me point blank: “Do you want your number to be added to the list?”

As a journalist who has been covering this pandemic for nearly a year, I knew how important it would be to get the covid-19 vaccine. My husband and I are in our 30s with no underlying health conditions, which puts us squarely at the back of the line. (Some states are pushing to include media workers in a priority group, but not Washington.)

I quickly went through the ethical gymnastics in my head. Under ordinary circumstances, would I be taking away someone else’s dose? Yes – those 1,600 doses were meant for someone else.

Do I have a moral obligation to protect others in my community by being one more person who was immunized? Absolutely – and others argue that it’s better for someone to be vaccinated out of phase than for doses to go to waste. If you decline, there’s no guarantee it will be given to someone of higher priority than you. Worse, it might be thrown out if it doesn’t get into someone in time. And in this particular moment, all those doses were on the line and had the potential to go to waste. I told my friend to put me and my husband down on the waitlist.

A few minutes later, my friend updated me by text: “My friend said we should just go and there may be a wait but we’ll get it. UW Medical Center – Northwest.” I just got out of the shower and haphazardly tossed on clothes. My husband, minutes away from going to bed, also rallied.

The northwest campus of the University of Washington Medical Center is a short drive from my house. I was there nearly a year ago, covering the novelty of drive-through test sites for the New York Times. I was struck by how many cars were headed for the vaccine clinic. A line of people had already extended outside the hospital.

A few minutes before we were about to enter the building, a medical worker came out with the tickets. At the deli counter, these tickets would have gotten me a sandwich. Here, the fading yellow ticket was a golden ticket—one that would get me one of the coveted vaccine doses.

Those of us with a ticket walked through the hospital’s winding corridors already lined with people who had arrived before us. I passed people who looked my age, some college students, and few individuals who looked like they could have belonged in the priority groups. I prayed that this late-night scramble in a poorly ventilated hospital hallway wouldn’t become a superspreader event.

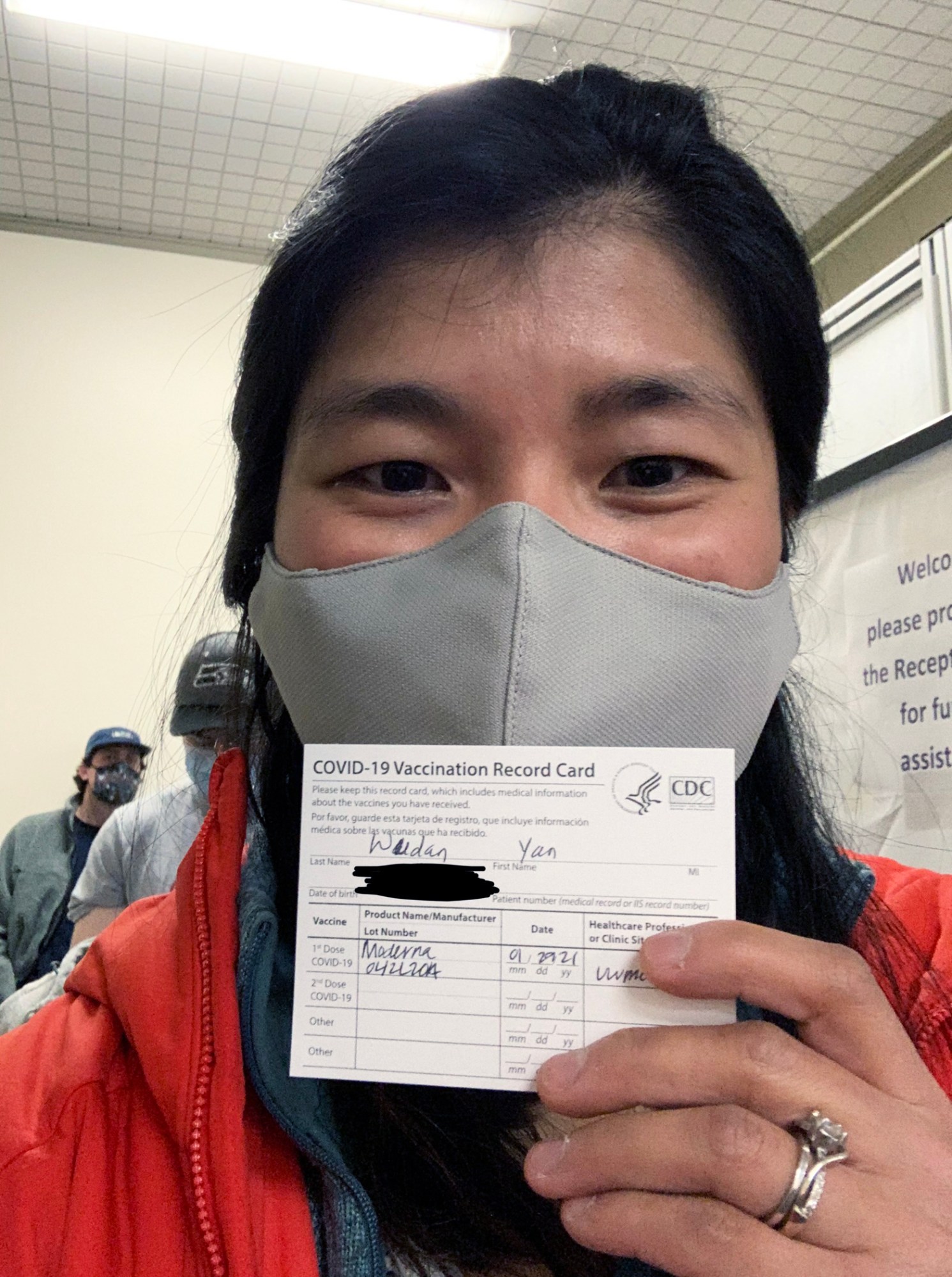

Around 11:26, a nurse told us they had started vaccinations. The line finally started moving fitfully, but steadily. At 1 a.m. on January 29, I received my first dose of the Moderna covid-19 vaccine. We waited for 15 minutes to monitor ourselves for any immediate post-vaccination reactions, and then left. The line outside had wrapped around many blocks by then.

While I was in line, I learned through Twitter that the expiring doses had been divvied among three local hospitals. They posted a call for appointments on Twitter, mostly looking for folks in the priority tiers. But doses were quickly expiring. At around 3 a.m., medical workers were looking to vaccinate anyone. A 75-year-old woman who runs a daycare left her house in a pair of flip flops. She was vaccinated on a street corner close to Swedish Cherry Hill.

What happened in Seattle was a repeat of what happened a few weeks earlier, when a freezer in a northern California hospital containing 830 doses of the Moderna covid-19 vaccine malfunctioned and the medical staff decided the best move to make would be to inject every dose into anyone available, regardless of their priority status.

In the aftermath of the late-night scramble to get vaccinated, I felt a strange mix of relief and guilt. I was relieved to be one step safer to the people around me in the community, all the while acknowledging that my social privilege, access to technology, and vehicle had given me a major advantage. If an incident like this happens again, which it very well may, given how sensitive these vaccines are, will those in line be more people like me: those with connections to healthcare workers, and who can drop whatever they’re doing and rush to a hospital?

Stephanie Morain, a medical ethicist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, says that even though we are better using doses than letting them go to waste, there are ways to use them to ensure that vaccine allocation doesn’t exacerbate these issues of privilege and access.

Some vaccination sites across the country have set up formal registration systems. “Community members can put themselves in a queue, and distribution is prioritized not by those who happen to know the nurse who is on shift that day, but instead based on the formalized criteria,” she says. “The latter, to me, is more ethically justifiable.”

Although what happened in the late-night scramble for a vaccine in Seattle was symbolic of many failures in the vaccine rollout, it showed us that when there’s a will, there’s a way. Doses were set to expire, and the community had to respond. Nurses and other frontline workers rallied to the call for volunteers to distribute vaccines almost immediately.

Toward the end of the night as the doses dwindled, one healthcare worker at UW Northwest said that she saw younger folks in line give up their spots to those who were older. By 3:30 a.m. on January 29, no doses went to waste. The circle of protection expanded.

Wudan Yan is a freelance journalist in Seattle.

There’s nothing worse than lighting a new candle and watching it sputter out, tunnel, or…

Discover how woven metal fabric transforms restaurant design with its versatility, from feature walls to…

Upgrading your workspace? Get inspired by design ideas for materials, lighting, and amenities, and tips…

In recent years, the global interest in peptides has surged due to their wide-ranging benefits…

Maximize your workspace without overspending. Explore practical ways to expand your office using smart layouts,…

Discover how to create a thriving STEM community through hands-on, collaborative projects that are perfect…